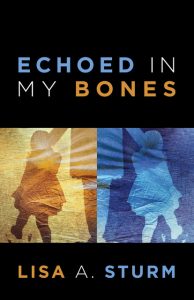

Lisa Sturm whose debut novel, Echoed in My Bones, by released by Twisted Road Publications on August 15, 2019. I’m particularly interested in her novel as I’ve raised a biracial son. Welcome, Lisa. Shall we chat about Echoed in My Bones?

SS: What in your childhood do you believe contributed to your becoming a writer?

LS: As the youngest of three, I was always an observer—watching what the older kids and my parents were doing. Mostly I was trying to figure out how to keep from getting in trouble, because back then corporal punishment was the norm, and my father … well, let’s just say he didn’t want us to be spoiled. So I studied my family’s emotions and tried to blend in with the wallpaper. I’m still fascinated by the whys of human behavior, and because I tried to keep quiet as a child, finding my voice as a writer has been tremendously healing.

SS: Do you have a day job? If so, is it a distraction, or does it add another element to your writing?

LS: I’m a clinical social worker, and this has inspired much of my fiction. The people I meet through my work are often fascinating. Every day I support others as they struggle with life’s challenges big and small, and in the process, I learn more about what it is to be human. When something seems unfathomable, that’s when I want to write about it. In a way, it’s how I make sense of the world.

SS: If you have children, does being a parent influence your writing? To what extent?

LS: I have three children and being a parent is not only a major part of my identity, it was a primary theme in my novel. Also, having written my first book while raising children, there were definitely family rituals and activities that found their way into that manuscript.

SS: Could you say something about your relationship to your fictional characters?

LS: I have deep love in my heart for my characters. There is a story told about E.B. White, who wrote many wonderful books, including Charlotte’s Web. When he was recording the audio version of the book, it took seventeen takes for

SS: Have any particular rejections inspired or motivated you?

LS: Yes, I received a very supportive rejection letter from literary agent Jane Dystel, who has represented Tayari Jones and Barak Obama! She said that both she and others in her office had read my entire manuscript and felt the writing was beautiful, the three interweaving stories well told, and the characters rich and developed. In the end, she didn’t offer representation, but that letter gave me the confidence and strength to continue on the long and rejection-filled path toward finding a publisher. I still have it saved on my computer!

SS: What was your first recognition/success as an author?

LS: In 2013 I entered a contest run by Writer’s Relief and won a Peter K. Hixson Memorial Award. The prize was three months of placement services for my short stories. Writer’s Relief sent out queries for me and as a result, several pieces were published in literary journals. I was over the moon!

SS: What are you working on at the moment?

LS: Lately I’ve been thinking about former patients who were in law enforcement and others who were in gangs, and I’ve been pondering the way personal history plays a role in decision making, particularly when people are under pressure.My next project is about a therapist, Delia Chase, whose drug-dealing client, Darnell, is murdered on the eve of his escape from gang life. In a desperate attempt to figure out how and why he was killed, Delia recruits another client, a police officer named Jimmy, to help.

SS: What is your most recent book? In twenty-five words or less, tell me why your book should be a reader should start your book next.

LS: Echoed in My Bones is about biracial twin sisters who are separated at birth and raised in neighboring towns, but worlds apart. It illuminates those things that bind us together, regardless of skin color.

SS: How did publishing your first book change your process of writing?

LS: After editing out over 300 pages, I’ve definitely moved from being a “pantser” to being a “plotter.” I’ll let you know how it goes!

SS: Regardless of genre, what are the elements that you think make a great novel? Do you consciously ensure all of these are in place?

LS: An interesting plot that builds—preferable with a new take on something, characters that really we really care about and that grow/change, and beautiful writing. If we learn something about people who are different from us or if it makes us consider our society in a new way, that’s even better! I do attempt to ensure that these things are in place when I write a novel, but it’s up to readers to determine if I’m successful.

SS: Do you write the kind of book you’d want to read?

LS: Absolutely!

SS: Lisa Cron (Wired for Story) says, “We think in story. It’s hardwired in our brain. It’s how we make strategic sense of the otherwise overwhelming world around us.” In what way are you trying to make sense of the world?

LS: I think I was definitely trying to make sense of my experience as an inner-city psychotherapist when I wrote Echoed in My Bones. I had heard many stories of trauma, abuse, and abandonment, but there were also inspiring moments of strength and resilience. I witnessed glimmers of hope and profound faith, even in the face of tragedy. All that was juxtaposed with my own privilege. This novel was a way of grappling with, and making sense of, that experience.

********************

********************

An excerpt from Echoed in My Bones

It had been almost two years since Lakisha had seen her mother—she remembered only a soft cheek pressed against hers and dark eyes that seemed ready to cry. Then, the summer before kindergarten, Maizy returned. She scooped Lakisha up off the thinning living-room carpet, squeezed her against a bony chest fragrant with lavender powder, and kissed her cheek with a cinnamon-gum mouth.

She reached into a blue-and-white striped bag and Lakisha stared at her slender, scarred arm. After a moment of fishing, Maizy pulled out a doll in clear plastic. “It’s from the South,” she said, like that made it special, and handed it to Lakisha. Aunt Dottie and Grandma Louema had given her other dolls, used toys with knotted hair or missing clothing. But this one, a brand-new doll all her own, she pressed against her ribs, her eyes lifting to her mother and beyond, as if it were Judgment Day and she had been deemed worthy.

“It’s a Topsy-Turvy Doll—it changes,” explained Maizy, pulling off the wrapping. Then Lakisha saw it was true. When she held it up one way, it was a black girl with a long red and white polka-dot dress and matching checked headscarf. When she turned the doll upside down and flipped the dress, it was fair-skinned with two blonde braids, a light-blue dress and matching bonnet.

“I love it!” Lakisha’s heart felt like a balloon filled to bursting, and she tried not to let her mother or the rag doll escape her sight. That night, Maizy climbed into bed with her, and Lakisha tucked herself beneath her mother’s arm. She held a fist-full of Maizy’s braids in one hand, and in the other she clutched the doll: the special one from the South, who unlike most people around her, had the ability to change.

Eleven years later, Lakisha leaned back on a birthing bed, her limbs still shaking from hours of pushing, her hospital gown plastered against her sweaty skin. She fingered the mattress until she found the topsy-turvy doll, now frayed and stained from years of loving. She pressed the raggedy treasure to her face, inhaling a memory—the scent of her mother. All that remained of Maizy was an image; soft skin over fragile bones, and track-marked arms that could hold you in a way that made everything bad in the world disappear.

The door swung open and banged on a rubber stopper. “You should’ve called me when you went into labor!” Aunt Dottie plowed into the room, her black umbrella trailing raindrops as it bounced against wide hips. “Damn Newark traffic; it’s a mess. Too bad your Grandma Louema didn’t live to see this—crazy about babies she was…even though you are way too young!” She shook herself, sending a small shower onto the speckled linoleum.

Dottie’s meaty body twisted around taking in the monitors and bloodied sheets peeking out of a laundry bin. “You all done? Where…” Dottie took a few steps toward a nurse who was moving back and forth between two pieces of equipment that resembled giant toaster ovens. Then she lifted a palm to her hazelnut cheek. “Lord!”

“I had twins. It’s all right, Auntie.”

“Uh, oh. This is not good!”

Dottie had a knack for turning situations sour; like her fat fists perpetually clutched lemons, and she stood ready to juice away anything sweet. The obstetrician who had delivered the babies entered the room, trailed by a few others in white lab coats who looked like students. The small group peered over the nurse’s shoulder as she worked. Their murmurings registered surprise, and a few glanced at Lakisha with wide-eyes before leaving.

“What is it?” Lakisha’s throat was parched, her voice gravel. She felt a wave of heat rise in her chest. “What’s wrong?” Maybe this time, Dottie was right. She hadn’t heard anything about the second baby other than that it was a girl—hadn’t even seen her. Did she have two heads? Eleven toes? A birthmark that looked like Jesus on her forehead? The first girl had a mark above her right cheek that resembled a half-moon. Lakisha hoped it wouldn’t make her ugly. But whatever was going on with the second one had to be even worse. “Auntie, bring me that baby you’re looking at!”

Dottie was usually the one who did the bossing, but this time she obeyed. Lakisha stared down at the small bundle. She unwrapped the infant and blinked several times, hoping to see something different. It couldn’t be…this had to be a mistake. She shoved it back into Dottie’s arms.

“Just a little surprise from the gene pool,” explained the nurse. “Most of us got some mix of blood. Blond hair can be pretty.”

Lakisha shook her head, trying to dismiss the truth that now clawed its way up into her throat. “There’s no way that one—”

“Don’t worry about the coloring. Babies can change—”

Lakisha stiffened. Her panicked eyes gripped the nurse, “No, no! That one’s not mine!” She paused for a beat, “The other one either!” She turned to Aunt Dottie, “You understand what’s happened, right? You have to help me! If they’re a set, I can’t keep them—they can’t be mine! They can’t be…oh, Theo.” She collapsed into the mattress.