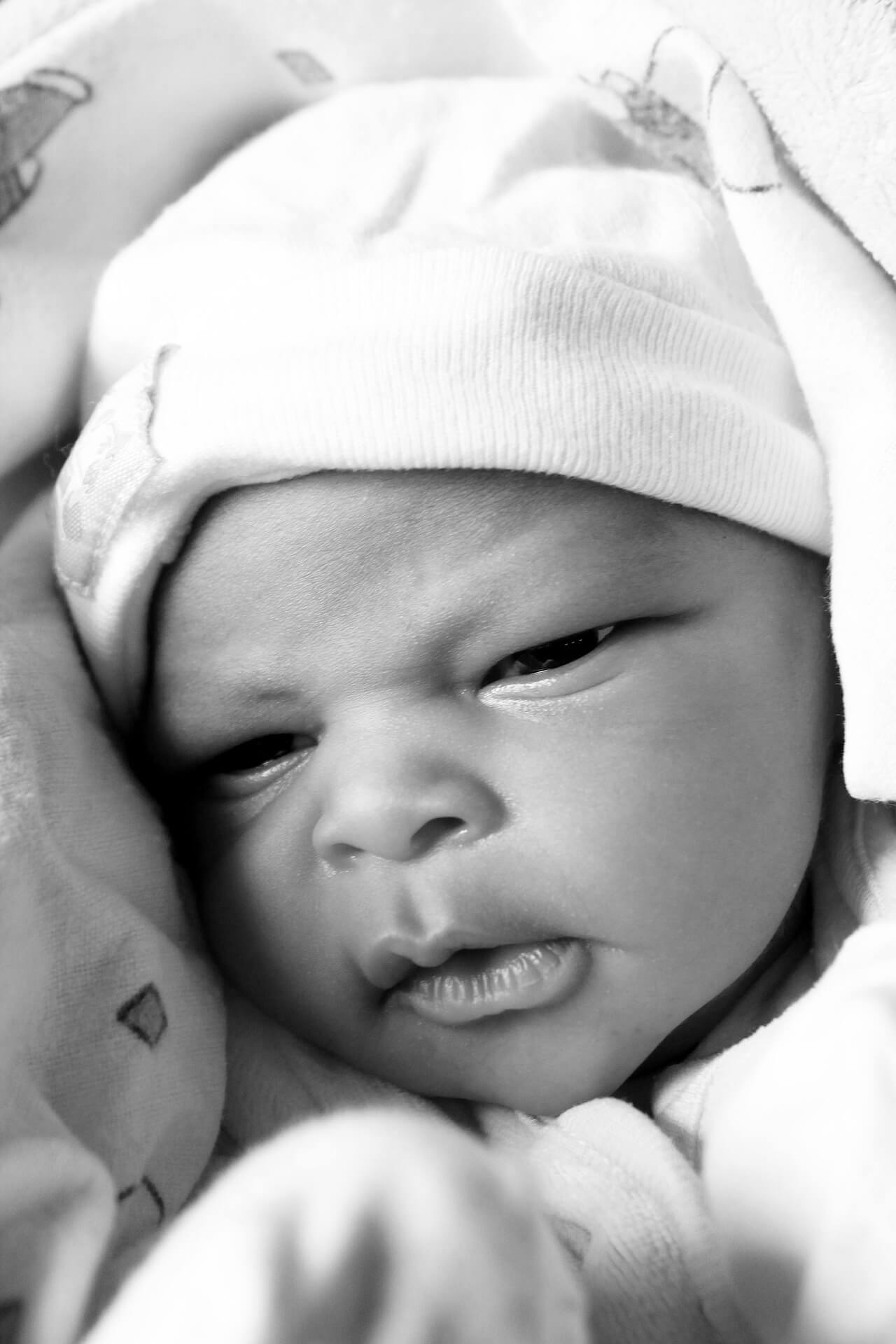

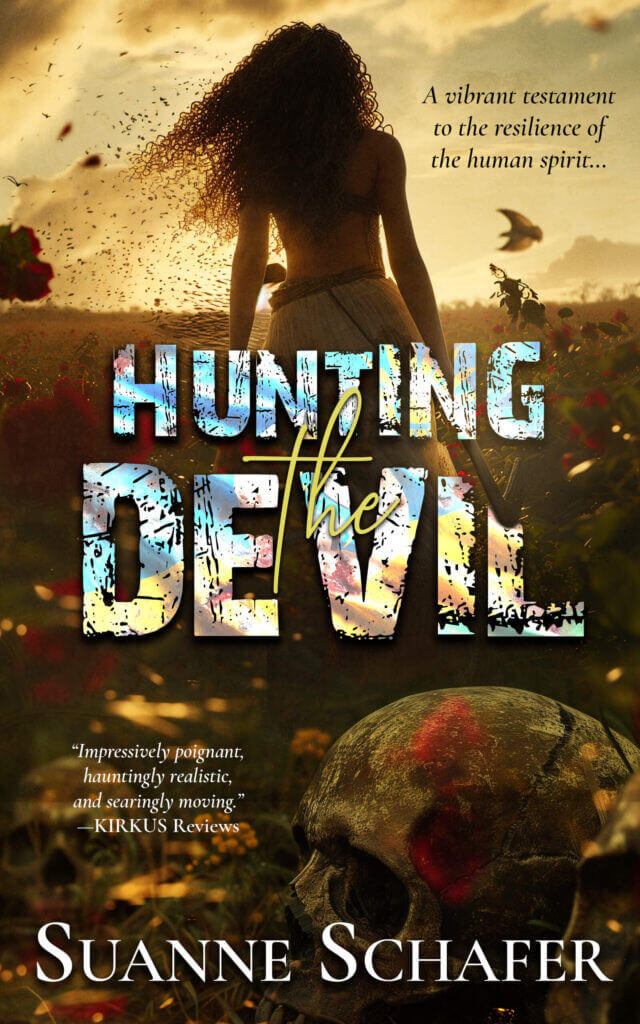

To mark the September 15th publication of my new novel, Hunting the Devil, I’ve updated a personal essay I wrote several years ago. It was originally published in Brain, Child Magazine under the title “Raising My Black Son.” My efforts to raise a Black child, combined with his difficulties sorting out his identity issues during our trip to Africa, sparked Hunting the Devil.

Twenty-four years ago, I adopted an interracial child—I’ll call him M here—thinking a mother’s love could overcome all barriers, even racial ones. Now I’m not sure I did my son any favors. I’m a White mom trying to navigate the ins and outs of raising a Black child in a hostile—and potentially lethal—environment.

M came up for adoption late in my fourth year of medical school, the unwanted love child of a sixteen-year-old White mother and a Black seventeen-year-old father. Unable to take her mixed-race baby home to her blue-collar family, the young woman kept her pregnancy secret from everyone except her mother then gave the baby up for adoption.

My family was tickled to have a grandchild, whatever his color. A second cousin had broken ground by giving birth to the first interracial child in the family, so M was not an oddity. My grandmother, however, frequently congratulated me on how “good” I was to take in a child “like that” even as she spoiled him.

As a physician, I often think about nature versus nurture and have found that, though we’re not genetically related, he’s clearly my son. We’re both rather shy but share a quirky sense of humor, a fascination with science ranging from dinosaurs to birding to stargazing to medical oddities, a dash of sarcasm, and the love of using just the right curse word to express our true feelings. We both love science fiction, Star Wars, and trying cuisines of various cultures.

Pensive teenager

Early on, I bought all the appropriate books on Black heroes—Rosa Parks, Frederick Douglass, and Martin Luther King— and tried to incorporate them into our daily reading ritual, but M was never interested. Unfortunately, Dr. King was not a Tyrannosaurus rex and therefore didn’t capture M’s attention. He remained singularly uninterested in Black role models. I marched in the MLK parade alone.

After completing my family practice residency, I interviewed from New York to California, including a small rural community in which M would have been the second Black person. Ultimately, I chose to practice in San Antonio, a culturally-diverse city where interracial families are common and where we would not stick out. Our family was also a bit of a “rainbow,” including a Filipino aunt and cousins. Thus, M grew up with friends of multiple racial and ethnic groups but seemed to choose his friends based on common interests rather than common skin tone. He freely admits being an Oreo, Black on the outside, White on the inside.

Fortunately, we had very few racial incidents as he grew up. The most blatant occurred as we ate dinner at a Chinese restaurant. A White man came to pick up his take-out, saw me sitting with my four-year-old child, and approached us practically spitting through his teeth, demanding “With all the White kids out there to adopt, why the hell did you adopt a nigger kid?” The Chinese owner of the restaurant, who certainly must have encountered racial barriers himself, apologized profusely then escorted the gentleman to the door and asked him never to return.

When he was sixteen, M and I went to Tanzania together. A camera safari was on my “bucket list” things to do, and M had some underlying, if ill-defined, desire to discover his African roots. There, though no clear-cut incident occurred, he seemed very uncomfortable. He’d never been in a place where Blacks significantly outnumbered Whites. Because he was clearly interracial and accompanied by an affluent Caucasian woman, he was considered a mzungu, a White person and was treated accordingly. Despite calling himself an Oreo, M found the role reversal quite disorienting.

We live in a predominantly White neighborhood with a goodly sprinkling of Hispanics, Asians, and Blacks. Yet Max came inside one day from checking the mail saying, “Mom, these folks in a car watched me until I got inside. Guess they were making sure I wasn’t breaking in.”

About that time, the news exploded with stories of young Black men in hoodies being killed. #BlackLivesMatter trended on social media after George Zimmerman was acquitted in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin, an African-American teenager the prior February. With M’s tendency to take long walks in the evening to blow off steam from raging male hormones, I grew nervous, treading a delicate line between making him fear life and teaching him to avoid potentially hostile situations, to never mouth off to a cop, to not wear a hoodie, to keep his hands visible and empty at all times, to back down in a confrontation. I suspect I was more worried than he was. Just a few days ago, I was awakened by sirens and the flashing of cop car lights. Immediately I checked that my son was safe at home and not out on one of his late-night walks.

On the Serengeti heading to our tent

For the past two years, he’s had a Hispanic girlfriend who looks white. For months she avoided introducing him to her parents because of his race. With the passage of time, however, he has been doing things with her family, and the racial issue seems to have become a non-issue.

Months ago, he hollered questions from the kitchen back to my office. “Mom, how much money did we make last year?” I raised my eyebrows at the “we” but gave him the figure he sought. After few more rather personal questions, I asked what he was doing. “Calculating my privilege.” A few seconds later, “I’m really privileged.”

He came to my office where I reviewed the questionnaire he filled out and suggested he give “real” answers, not those based on his White physician mother’s income, education level, etc. The findings: he was an unemployed Black male who dropped out of college and therefore—surprise!—had no privilege.

A blue-collar child, I grew up with little privilege. My father worked as an itinerant well logger in the oil field. By the time I was twenty-four months old, I’d lived in twenty-two towns across the western United States. Over the years, I attended three fourth grades, three seventh grades, two ninth grades. I graduated from high school and put myself through college with scholarships and by working full-time and going to school part-time. I picked cotton, worked as an aide in a nursing home, roofed and painted houses, clerked in a book store, did piece work in a toy factory. Later I became a medical transcriptionist, then a travel and medical photographer. I continued the wanderlust bred into me and attended four colleges and traveled abroad before attending medical school. By the time I graduated from medical school, my parents had contributed a total of $275 to my education.

Knowing how hard it was to juggle work, school, relationships, and life in general, I wanted M to have an easier life, easier access to higher education. As a result, he’s had every economic and educational advantage possible. I realized he was intelligent but having trouble focusing; however, the school district refused to believe he had ADHD because he was doing well. A private psychologist tested him and verified my diagnosis and added a few of her own: ADHD, dysgraphia, and a borderline learning disability in mathematics hampered his abilities. Once he was diagnosed, medications to tone down the ADHD turned him into a grumpy kid and completely suppressed his appetite. I fought yearly battles with our school district because they consistently failed to follow the learning plan set out by his psychologist. Eventually, I filed a lawsuit against them. I lost the case. The reason: children are merely guaranteed an education, not necessarily a good education.

Coupled with the learning problems, unlike his mother, he’s simply not a “driven” person. A procrastinator par excellence, he’d rather play video games than anything. I keep telling myself this must be his inherent nature, because he certainly wasn’t nurtured to be lackadaisical.

At this point I am the mother of an unmotivated child, one who despite having a substantial college savings account, does not wish to attend college. He’s also a Black child raised in a White family. He has “White” expectations of earning a upper class income, being housed, clothed, and well-fed consistently. I’m not sure he grasps what it means to be Black in America. I’m equally unsure I can teach him that, or perhaps it’s too late to do so.

M is a good young man, a success in that he graduated from high school at a time when 40% of children expelled from school are Black, when 70% of children arrested are Black or Latino, when Blacks are twice as likely to drop out of high school, and when two-fifths of Black children live below the poverty line. He’s sexually active but not promiscuous, doesn’t abuse drugs or alcohol, has never been in trouble. Except for an occasional outburst of testosterone-related temper, he is caring, even-tempered, and sweet.

I’m coming to terms with the idea that M has to make his own mistakes. Letting go has been hard. I am getting better at it, learning to offer support, rather than fighting his battles for him. He moved in with his girlfriend in a town thirty miles away, so I can no longer micromanage his life, a fact that I suspect made us both happier. He’s getting married in November, having chosen a young woman who is as sweet as he is. I couldn’t have chosen a nicer daughter-in-law had I hand-picked her. At some point, he’ll be a good father, but due to the procrastination issue, not necessarily a good husband as he’ll put off doing household chores as long as possible. I am trying to let them make the wedding plans and only offering advice if asked.

Mostly I hope that, at some point, M can reconcile the duality of his heritage and can integrate his chocolate-cookie exterior with his creme-filling interior. I pray that American culture will evolve to the point “White privilege” no longer exists. That a Black man can be simply a Black man without negative consequences. That a Black man can earn what a similarly educated White male does. That Black children will have true equality of education. That a Black man should not have to be a superman to be equal to a White man. That every Black male has the equal opportunity to become the best person he can be.