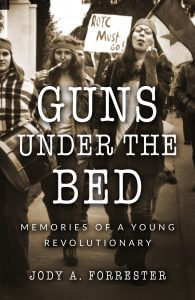

Jody A. Forrester and I are both “women of a certain age.” She was born and raised in Los Angeles during the uneasy Fifties and tumultuous Sixties; I was raised in conservative West Texas during that same time frame. She graduated from high school in 1969, when the Vietnam War was raging and the country increasingly divided along racial and class lines. While a freshman at San Jose State University, she joined a communist organization advocating armed overthrow of the United States government. In Guns Under the Bed: Memories of a Young Revolutionary, Jody reaches into her past to understand how she came to embrace such a violent culture. She lives in Venice, California with her husband, John Schneider and Australian Shepherd Charley, in the house by the beach where they raised their two daughters, Emily and Erin.

Jody’s memoir, Guns Under the Bed, will be released today by Odyssey Books, Her essays and short stories have appeared in the Sonora Review, Two Hawks Quarterly, WriteRoom, Dreamers Writing, Citroen Review, Gazelle and several others. A story received an honorable mention in the Anderbo/Open City Competition (2009) and another story was featured in the 6th Annual Emerging Voices Group Show (2010) in Los Angeles.

I’m happy to welcome her to this interview.

SS: Jody, what was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

JAF: I might have been four or five when I began reading chapter books. They revealed a world different from my own which both titillated and excited me. Up to then I assumed that the world that I knew was all there was, but language freed me from the burden of those beliefs and I’m forever grateful.

SS: Can you share a bit about your background?

JAF: I grew up in Hollywood in the fifties and sixties, right in the center of the cultural upheaval that pervaded the zeitgeist. An active member of the sex, drugs, and rock and roll generation, it influenced the decisions that I would make throughout my life. My parents were middle-class, I attended very good public schools, and yet always felt unsettled and on the margins of both my family and society at large.

SS: Writing is undoubtedly a lonely occupation. John Green (The Fault in Our Stars) says writing is a profession for introverts who want to tell you a story but don’t want to make eye contact while doing it. P. D. James (Cover Her Face) says it’s essential for writers to enjoy their own company. Do you see yourself along those lines? Are you a natural loner?

JAF: As a child and adolescent, my sense of self was very much defined by a deep desire to embed myself in a social group. That seems a long time ago—for the last many years, I have indeed become a loner with only a few close friends. I think that is a natural state for me, my earlier self more driven by the insecurity I felt at home.

SS: How long have you considered yourself a writer? Did you have any formal training, or is it something you learned as you went?

JAF: I’ve always dabbled at writing but for lack of self-confidence, didn’t take it seriously. It wasn’t until an injury sidelined my profession as a chiropractor that I took at close look at what should come next, and the answer came easily. I would write—but I had a lot to learn. To that end, I attended Antioch University in Los Angeles for a creative writing and literature BA and Bennington Writer’s Seminars for a MFA also in creative writing and literature.

SS: Who do you consider to be your biggest and best mentor and/or inspiration?

JAF: Samantha Dunn, an educator, writer, and journalist in Orange County, has definitely been the one person who guided me as a writer. I wrote my memoir under her tutelage, and her support and advice is invaluable—I couldn’t have written the book without her.

SS: Which non-literary piece of culture could you not imagine your life without?

JAF: Art—museums are always the first places we visit when my family travels

SS: Me, too. My grandmother was an artist and I’ve worked in oils, watercolor and egg tempra—and the fiber arts of knitting and quilting. If you could have been the original author of any book, what would it have been and why?

SS: When you are creating a story, do you avoid reading books in the same vein so as not to be influenced by others, or do you seek out all possible variations for maximum inspiration?

JAF: Actually, the opposite. While writing Guns Under the Bed, I devoured dozens of memoirs, mostly to see how their authors went about crafting such personal stories.

SS: I took a memoir class in Stanford University’s creative writing program, and learned that I didn’t like writing memoir. What is your writing Kryptonite? What’s most likely to stop the flow of your words?

JAF: A lack of confidence—freezes every time

SS:What other authors are you friends with, and how do they help you become a better writer?

JAF: Ginger Eager and Lili Flanders. Both have been supportive critical readers and their feedback consistently opens my eyes to what needs deepening and what is missing. I feel very lucky to have them in my life.

SS: What works best for you: typewriters, computer, dictation, fountain pen, or longhand?

JAF: My handwriting is atrocious, and it’s often the case that I can’t read it myself. I began writing on a typewriter, and now am happy to use a computer where I can save multiple drafts, delete, and add a sentence here and there as needed.

SS: Which scene did you find the most challenging to write and why?

JAF: The first chapter I tell about a time when a group from the Revolutionary Union, the communist organization I was a part of, sat in my living room with guns aimed at the front door in anticipation of a police raid. The question that drove the writing of this memoir is would I have pulled the trigger if, indeed, they came in? For years that troubled me, because I truly do not know the answer. How could I not have when I was eighteen and under the influence of a powerful ideology? It’s been hard to accept that I’ll never really know.

SS: Do you believe you wrote the kind of book you’d want to read?

JAF: That certainly was my intention. I’m very curious about that era of protest and have ready many books about it. I think mine would be on that list.

SS: What was the first book you fell in love with?

JAF: The Black Stallion by Walter Farley. The best—I read it and his other books dozens of times.

********************

********************

An excerpt from Guns Under the Bed:

Prologue

On a morning in 2010, I went into the garage determined to get rid of the old to make room for the new. Dozens of boxes, some unopened since our move in 1985, leaned against each other in precarious piles. Green garbage bags ofour now-adult daughters’ stuffed animals, board games missing pieces, drawers full of the wooden-handled tools inherited from my father—all of it could go.

I tugged first on the plastic handle of a one-wheeled suitcase with a broken zipper, but something caught. Pulling harder, a large carton lying against it tipped over. Labeled “RU stuff,” it had traveled with me from San Jose to Vancouver B.C. to Los Angeles, stored always somewhere out of sight. The bent and frayed box contained over three years of my late adolescence, chronicling the only period of my history that remained unexamined in a much-examined life.

When it hit the ground, out tumbled magazines, newspapers, and documents I’d accumulated from 1969 to 1972 while a member of the communist Revolutionary Union (RU). Sitting on the paint-stained cement floor, I thumbed through proclamations and calls for political action as well as national and international newsletters from those times. Minutes from RU meetings, internal memos, leaflets for demonstrations and marches—I hadn’t realized that I’d kept so much. There in the pile was a much-thumbed, underlined, and highlighted Little Red Book with Mao Tse-Tung’s many quotations of how to put theory into practice.

Two photographs fell face up on the garage floor, one taken while I sat at the Revolutionary Union information tableerected daily outside the student union at San Jose State College. I’m wearing a navy blue Mao cap replete with red star, my downward gaze pensive, quiet, wary of the camera. Maybe eighteen, to me now I look impossibly young. The other picture was a Polaroid of a group of us marching on the sidewalk, me in front blowing a kazoo,holding a sign that read “ROTC MUST GO!” My middle finger pointed defiantly up. I’m wearing my favorite poncho, red with a Navajo pattern crossing the middle, a kerchief holding back my unruly hair. Again, I look so young, however old I felt at the time.

Evidence surrounded me of those years when I slept with a 30-ought-6 and a M1 rifle under my bed. So many in mygeneration protested the unjust war in Vietnam and marched for civil rights. How was it that I was one of only a few hundred who went on to join an organization with the most extreme of ideologies? How was it that I was so willing toput my life on the line, a life I had yet to value? Youthful conviction born of the zeitgeist of the times or something missing in myself that I sought to remedy? While it’s true that much of the Baby Boomer generation felt displaced andalienated by the establishment mentality, why me?

I decided it was time to reclaim those lost years, to learn more about how I got there, and how I got from there to here. Ready finally to release the stories the box held, I loaded it back up and took it into my office to begin the work.