I was born and raised in Big Spring, Texas with time off for moving throughout the western United States as my father, an itinerant well-logging engineer, followed oil wells from state to state. Most of my family stayed in West Texas and ranched near Big Spring or Garden City. Later, they raised cotton or sheep. Tough folks, they survived dust bowls, droughts, and oil booms.

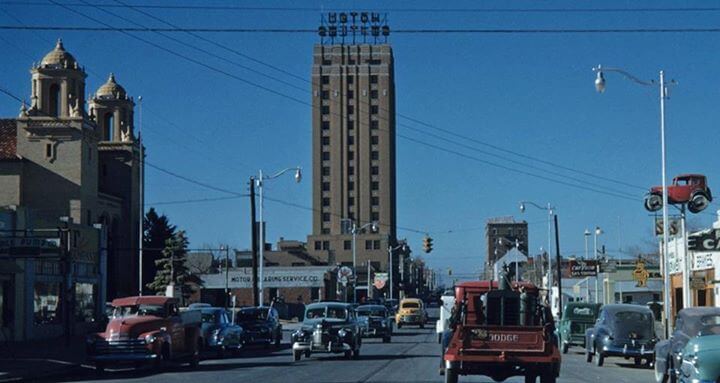

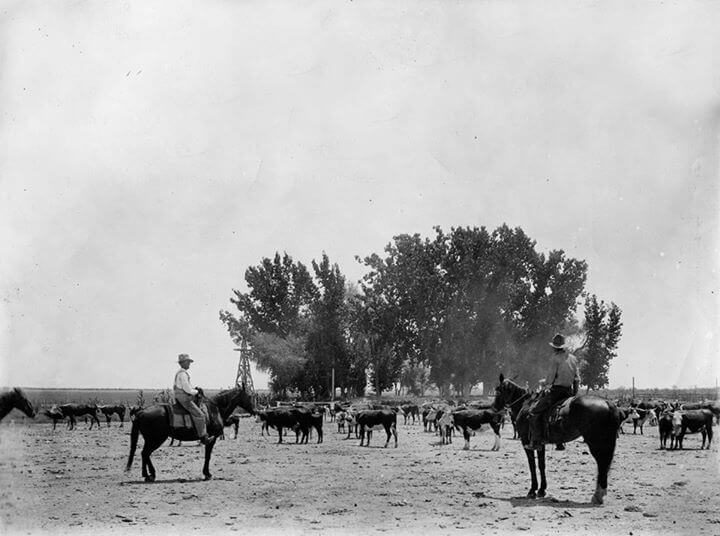

By the time I was twenty-four months old, I’d lived in twenty-two towns. But I have fond memories of visiting my grandparents in Big Spring. My paternal grandfather parade me up and down the block in front of the feed and seed on Wednesdays when they came to town to stock up on ranch supplies at the feed and seed and hit the Piggly Wiggly for groceries. Even in the late 1950s, I remember going to cattle roundups still done on horseback.

My family was tough. They survived droughts, dust bowls, oil booms—and the Great Blue Norther of 1911 when temperatures dropped up to 70 degrees in hours, and rain, hail, sleet, and snow all fell in less than two hours.

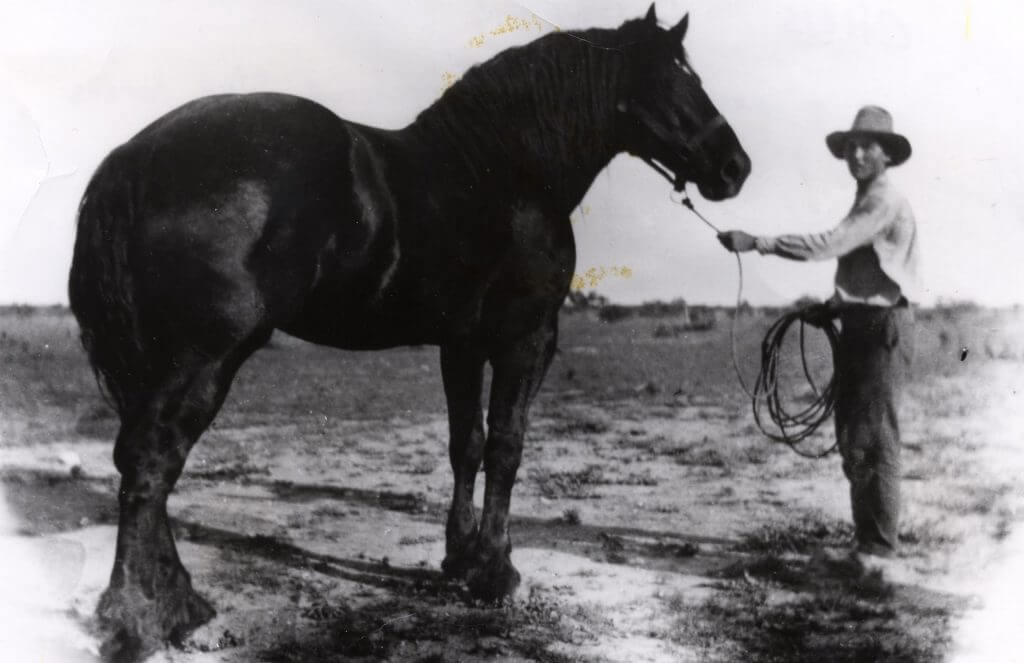

After the introduction of windmills (which allowed settlements outside of areas with where a constant water supply already existed) and barbed wire (which ended long cattle drives), ranching—and a ranch wife’s life—didn’t change much from Ruby’s time through the mid 20th century, though cars and trucks slowly replaced horses. My grandparents—like Ruby and Bismarck—nearly divorced over whether to install indoor toilets. Men milked cows by hand by the light of kerosene lanterns while their wives slaved away at a wood range and washboard. My grandmother, like Ruby, gardened, canned vegetables and meat, sewed, knitted, ironed, and much more.

By the 1890s, cities like Houston, San Antonio, El Paso, Dallas/Fort Worth and Austin were aglow at night from electric lights in homes, yet nine out of ten rural homes had no electric service. In 1935, Roosevelt signed Executive Order No. 7037 establishing the Rural Electrification Administration (REA). A year later, the Rural Electrification Act was passed and the lending program that became the REA got underway. In the early 1950s, telephone and electricity finally came to the family ranch. My grandfather had generators but lacked the mechanical skills to keep them functioning. The utility companies ran the cables, but the ranchers had to dig the holes and raise their own power and telephone lines. Once the lines were up, my grandmother raised parakeets in the shed that had housed the generator. When my grandfather sold his cattle in the mid 1960s, he became addicted to soap operas. God forbid anyone interrupt As the World Turns.

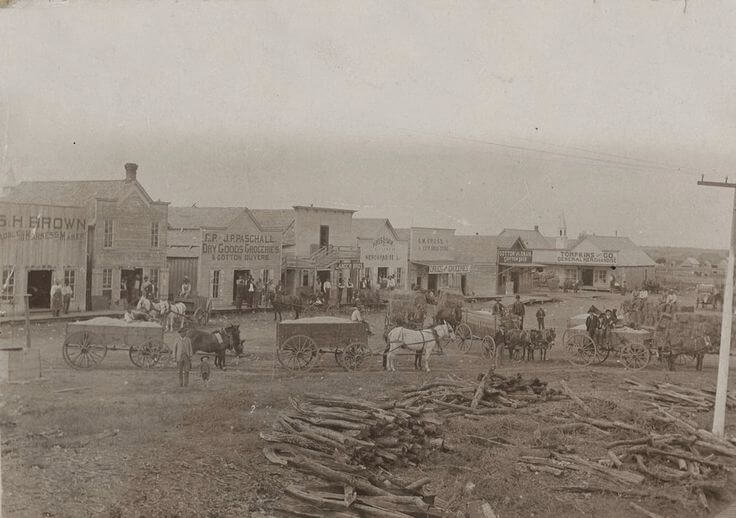

Truly, the setting of A Different Kind of Fire, is an amalgamation of numerous little towns sprinkled throughout West Texas: Garden City, Stanton, Sterling City, or Fort Stockton.

Truly’s highlights include Statler’s Mercantile where a hand-painted sign advertises Groceries—Ranch Supplies—Dry Goods—Clothing as bangs out a welcome against the eaves. There’s also the red-brick school house Ruby and her sisters attend during the 99-day school year while living in a little shotgun cottage with their mother. The ranch is too far away from town to be able to attend on a regular basis otherwise.

Helles’ Belles is the local brothel, located just outside town. The local madame had commissioned Ruby to paint a fancy portrait of herself au naturel—though discretely draped with velvet and lace—to hang above the bar of the establishment.

Several churches vie for members, but the one Ruby has the most contact with is the Mexican church of Our Lady of Guadalupe. In it, she finds comfort in her grief over her stillbirth and the breakup of her marriage. To show her gratitude, she paints a series of paintings to mark the Stations of the Cross. I envision Our Lady of Guadalupe looking like this tiny jewel in the ghost town of Calera near Balmorrhea State Park.

I hope you enjoyed this quick tour of one of A Different Kind of Fire‘s settings. Next time, Philadelphia and its effects on Ruby Schmidt.