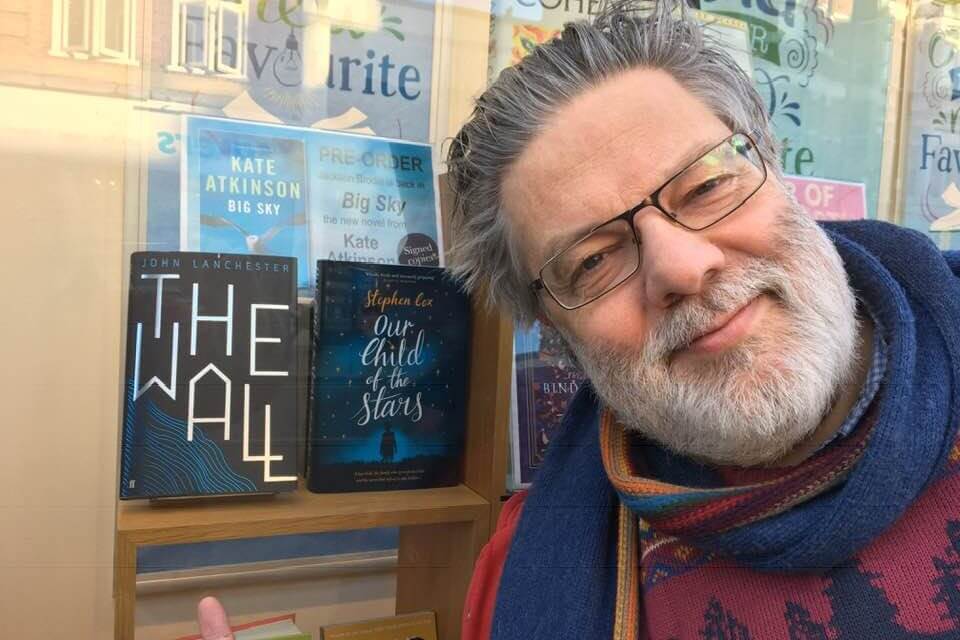

Stephen Cox and I are meeting in a virtual, therefore social-distance-safe interview. He was born in America of British parents, spent nearly his entire childhood in Bristol in the West of England, and now lives in London with his partner. His son has left home and his daughter will soon. He’s a professional communicator, a science PhD dropout, a recovering poet, and a Quaker.

After vaguely wanting to be an author for most of his life, Stephen actually wrote a novel in 2012 and in 2013 wrote a short story in a week which was the living seed for Our Child of the Stars. He aims for strong, believable characters and relationships. Life is often dark and unfair, but he writes with hope and humour. His work often has some speculative or fantastical elements.

He’s not the sculptor, the American Libertarian and expert on Jane Austen, or the guy who wrote a book about the Munchkins.

So Stephen, you’ve told us some about who you are and who you aren’t. Now, tell us about your writing.

SS: What is your most recent book? In twenty-five words or less, tell me why a reader should start your book next.

SC: Our Child of the Stars. Sixties, small town USA, Gene and Molly adopt injured orphan Cory. To keep him safe, they must keep him hidden.

SS: Regardless of genre, what are the elements that you think make a great novel? Do you consciously ensure all of these are in place?

SC: Characters that leap off the page and that you care about, situations that do not feel contrived. For me a world which acknowledges the dark and unfair side of life but addresses it with hope and humour. Voice. The sort of writing that takes you by the hand and says, Trust me, this will make sense in the end. This will be worth the journey.

I guess I truly want ‘heartfelt, richly imaginative and gripping’.

Yes, I try to write that.

SS: If you have children, does being a parent influence your writing? To what extent?

SC: I have two amazing kids—a son and a daughter, 22 and 18. When people ask me what Our Child of the Stars is about in one word, I say parenthood—its joys, the details of its frustrations, its costs. What loving someone more vulnerable than you means, and what it does to you. People connect with the book because it’s about being a parent, a friend, a child.

SS: Do you write with an imaginary reader in mind? If so, tell as a little about that person.

SC: Well, I didn’t consciously write the first draft for anyone. Now, years later, I write for women and those men who happily read books written by women. Compassionate, thoughtful, not scared of ideas but wanting something grounded in people and their experience. Willing to think and feel deeply. Readers, obviously. These people are not imaginary—my daughter, D and H my sisters in law. My wife says Molly is the best female character she has read in ten years. I have a good sense of what the book’s readers liked.

SS: Do you generally write in one genre? If so, what is it?

SC: Most of what I write has some speculative or fantastical element, even if lurking at the edge. Our Child of the Stars qualifies as science fiction because of who Cory is. Fantasy fans really like it too, it is enjoyed by people who aren’t science fiction and fantasy (SFF) readers. Of course, being unusual, it can have too many explosions for some and too few for others.

The conventional stories I write still have an odd twist to them somehow.

SC: I know I do. Does anyone spend years of their life writing something they wouldn’t enjoy?

SS: Writing is undoubtedly a lonely occupation. John Green (The Fault in Our Stars) says writing is a profession for introverts who want to tell you a story but don’t want to make eye contact while doing it. P. D. James (Cover Her Face) says it’s essential for writers to enjoy their own company. Do you see yourself along those lines? Are you a natural loner?

SC: It’s true that I’m comfortable with my own company and that writing requires lots of time at the laptop. A friend once said, being a writer does mean setting yourself homework so you can’t go out and play.

As a kid, I read voraciously and told myself stories, and I had relatively few friends until my early teens. A large gathering of unfamiliar people is tiring.

But perhaps we make too much of this. From twelve I found myself groups of interesting people I hang out with. In some situations, I find myself more extrovert. Writing is one of the things that gives me friends twenty-five years younger than me.

With this darn virus, I miss having coffee with my mates.

SS: Science fiction seems to be a great way to “hide” commentary on current political or social issues in a narrative. Do you think political statements belong in literature? Would you write a novel that was a political tract?

SC: Lots to unpick there! Science fiction holds up a mirror of imagination, which in distorting, shows a truth. But all fiction has the capability to throw light on our current society, even if by omission and emphasis.

I sweated blood so that Our Child of the Stars is not a tract.

One of the unexpected things about writing a book set at the end of the Sixties was how much of what I wrote threw light on what is going on now.

I remember reading The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, and ‘improving’ books sent by my godfather, and stopping dead when the author got onto the soapbox or the pulpit. (I picked Narnia back up though.) And sometimes you pick up a book, realise that it’s a lecture pretending to be a novel, and put it down again.

For me, a novel needs great characters, put in situations that challenge them. The commentary needs to arise from the story, because it is the story that matters.

A common mistake is to make villains unbelievable members of Team Bad, boo boo boo. A better writer illuminates positions opposed to the message, if there is one. In The Girl With All the Gifts, Mike Carey outlines a character who does unspeakable things to children, because she genuinely believes it is the only way to save the human race. We see exactly how she can think that, so much we fear she is right.

One of the big themes in Our Child of the Stars is that the parents Gene and Molly are idealistic, leftish, against the war in Vietnam, neither is religious… (but they are those things in human messy ways.) And in their direst need, they find friends and allies who are not those things. We find decency in people who don’t agree with us. I don’t have anyone climb into a pulpit and say that though a bullhorn. I let the point make itself.

Cory is an innocent from a society which handles some things very differently. He fits into the long history of stories where the outsider casts a kind but deeply critical eye on the way humans (like me) can do things.

SS: In the Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula K. Le Guin says that “science fiction is not prescriptive; it is descriptive.” Do you agree with her?

SC: One of the all-time greats. Yes. Some writers tout the idea that science fiction has a unique ability to predict the future and that it is rigorously scientific. Harlan Ellison described the predictive ability of the genre as a hundred drunks in a dark field at night, firing off shotguns. Sure, someone might hit the barn.

Science fiction can be prophetic, much less a clear path to the future, more passionate commentary on the possibility. Look, this could be what happens! 1984, the Handmaid’s Tale, Brave New World, are not accurate predictions, but we understand the truth of the warnings they contain. It can also point to generous, open, compassionate futures where, for example, we don’t blow each other up or trash the planet.

Le Guin also wrote that she ‘wasn’t interested in the plumbing’. No page long descriptions of how the flux capacitor works for me or her.

SS: What works best for you: typewriters, computer, dictation, fountain pen, or longhand?

SC: I write fast on a laptop, revise a lot, edit one draft on paper if I can. For me I must get a shoddy draft down. The writing throws up questions to answer, aspects of character to explore. The first draft is a great exercise in really knowing the characters. Stravinsky said the magic happens at the keyboard. If you fashion each sentence like a Swiss watch, you will have a different process. Fine by me.

SS: Was the decision of how to structure the novel obvious?

SC: My agent suggested a simpler structure, told in fewer voices, and I am eternally grateful for that advice.

SS: How do you give back to the writing community?

SC: I’m grateful beyond belief for kind words (and the odd blunt truth) given by more experienced writers, agents, publishers. I give back through membership of fantastic writers groups, one in real life and a few online. Advice offered in humility by a debut author on my website etc. Ad-hoc support of individuals.

SS: Name five things you wish you’d known before you published your first novel.

SC: It’s like parenthood, people tell you things, but you don’t believe them until it happens to you.

- One book published is not the Golden Ticket to own the chocolate factory. It’s getting to the mountain pass and seeing there’s another mountain, bit higher and you have only half the time to climb it.

- You were needy and neurotic before? Welcome to the next level. It’s a rollercoaster.

- Publishing is full of lovely people passionate about books. They say lovely a lot.

- A book can have ‘lovely’ reviews and yet disappoint commercially. In fact most debuts disappoint in some sense.

- Authors form a circular firing squad, A envies B’s cover, B wishes they’d got that review C got, C feels D tackled her themes better, D sees E has a film option, E feels in their guts A is a better stylist. Most authors quickly realise, be kind and supportive to everyone else.

- Sometimes, it is totally as cool to be published as you hoped. Six things, so sue me.

********************

Our Child of the Stars is available through:

Amazon | B&N | Indiebound

********************

Excerpt From Chapter One, Our Child of the Stars:

Molly sat by her bedroom window, sewing Cory’s Halloween costume. Looking out, Crooked Street was warm in the soft sunlight. Soon the old porches would shine with pumpkin lanterns, heads of orange fire with their savage grins. Long ragged witches and skeletons hung from the gutters and swayed as the wind ruffled the leaves of yellow, red and brown. She loved the sad beauty of fall, the possibilities as summer left and winter came.

The Myers house had been full of Halloween for days. The three of them carved pumpkins while sugar girls wooed their candy boys on the radio. Gene and Molly had enjoyed days of Cory’s endless chatter, and making things from painted leaves, and Molly’s attempts to bake new things from her old Joy of Cooking book. Cory couldn’t decide between a pirate and a sorcerer, so Molly said at last, ‘Be both.’ He flailed his arms in excitement. Then he saw how much gold braid she brought back from the shop – two double fistfuls – and he ‘want it all-all Mom.’ Red and gold – Cory never did half-measures.

There was so much small print in being a mother, like racing to finish the costume because not disappointing him mattered.

Cory got so antsy and up close, she couldn’t sew straight around him. She retreated to the bedroom, with the chair propped under the handle. Gene thought that when he found time he’d mend the lock, but it never quite happened.

As a child, the Jack-o-lantern was a familiar friend, and yet it still brought a shiver as night fell. Little Molly had loved dressing up as someone else, staying up late to hear scary stories, eating more candy than was good for her and running through the back streets at dusk, kicking up dry papery leaves. She could pretend twisting shadows were real horrors. The years passed and Molly put Halloween away, like a favourite toy in an attic box. She still loved fall when the year ran downhill to the dark.

In time, adult joys and adult fears came instead: her first job, a wedding song, the house. And a death.

She shook off a cold shudder. There were things to do.

Cory had come: their son, their miracle, and Gene and Molly had found so many things again. Snow angels and Christmas stockings, birthday surprises and fireworks on the Fourth of July. Cory would squat to look at some tiny green flower or stand entranced by the song of a single bird. He adored the day of disguises; he was made for Halloween and it was made for him.

As she sewed, Molly heard him outside in the hallway. That eerie creak could only be Cory swinging from the fold-down attic ladder and the little pad, pad, pad was him running along the corridor and back. You could never mistake that tread for anyone else. Sometimes all went quiet, which might mean Cory was hanging off the stair rail, upside down, to see how long he could do it. He might be out of the attic window and up onto the roof with his telescope, like some pirate up the mast. Cory often looked out across Amber Grove, official population 18,053 and proud of it, gazing north to the forest with its strange scar.

‘Safe Mom, look. Cory too clever to fall.’

But she didn’t think he’d fall. It wasn’t falling that frightened her.

********************

You can follow Stephen Cox here on social media:

Website | Twitter | Facebook | Newsletter

This post contains Amazon Affiliate links.